Once upon a time, the twist was a dance craze made famous by Chubby Checker. The 1960 hit inspired the dancer to maneuver the balls of their feet back and forth across the dance floor. But this past week, the Federal Reserve launched it’s own twist – that is, with the implementing of Operation Twist.

Operation Twist is a jaunty name for some fiscal maneuvering that, if successful, will lower interest rates and encourage people to invest and borrow more.

How, exactly, would that work? Smart Money had an expert explain it quite succinctly:

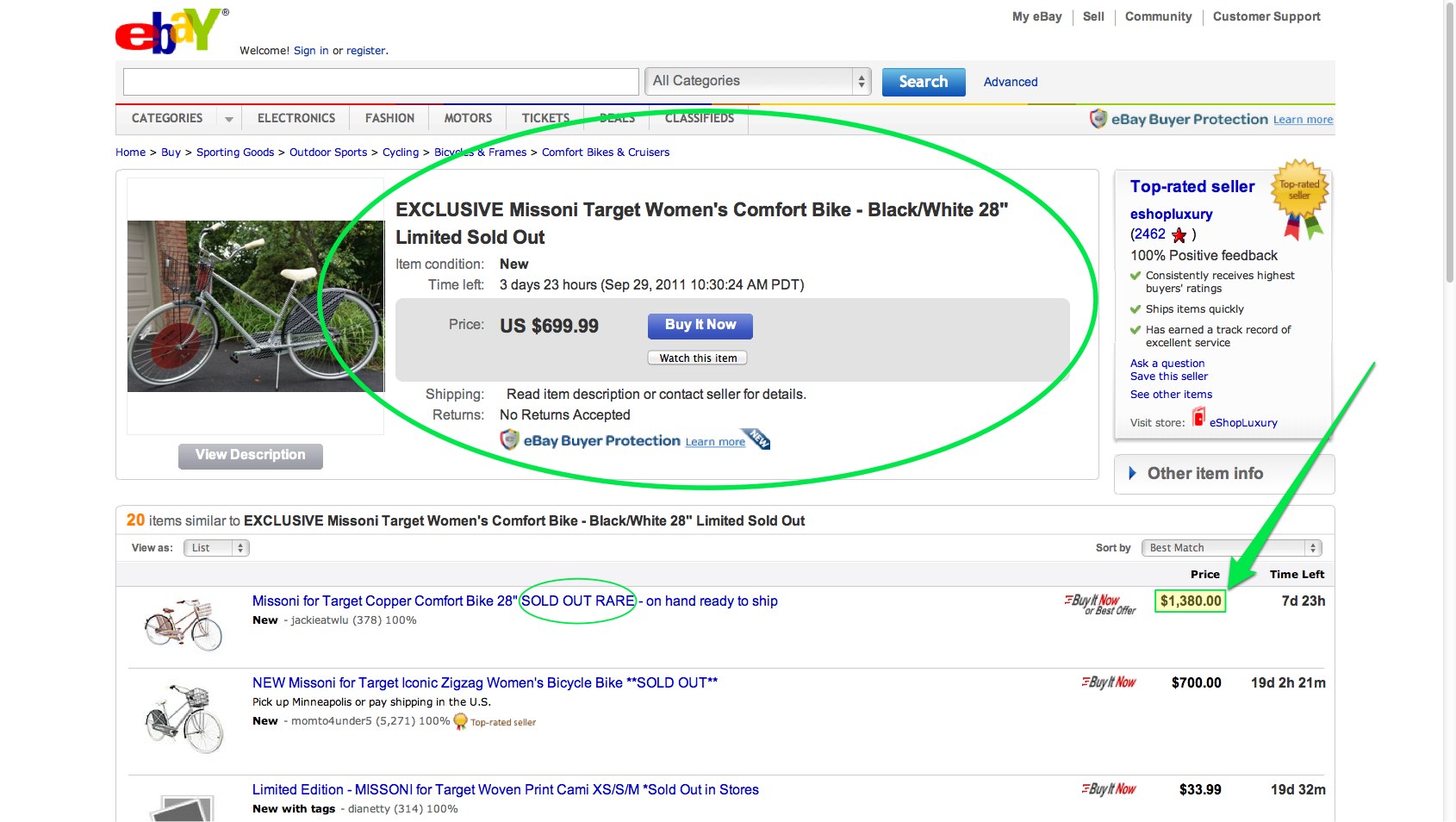

The plan is simple: the Federal Reserve would sell over $400 billion worth of it’s short-term bonds and use the proceeds to buy up longer-term bonds. At first, anyone who has long-term bonds will see their value rise. As time passes, the act would drive down the interest rate on the longer-term bonds (When demand for bonds rise, interest rates fall.)

Interest rates on long term treasury bonds are connected to many other interest rates in America, such as mortgage rates. The hope is that the lowered interest rates from Operation Twist would encourage borrowing and investing.

Robert Smith of NPR has a great step by step explanation of the process here:

Operation Twist is not a new idea, nor is it even a new title. The plan for the federal reserve to buy up bonds to “twist” the interest rates for investors was first proposed in 1961 by the Kennedy Administration, and was named for the popular dance craze at the time. Most people now consider it a failure.

But how about this time around?

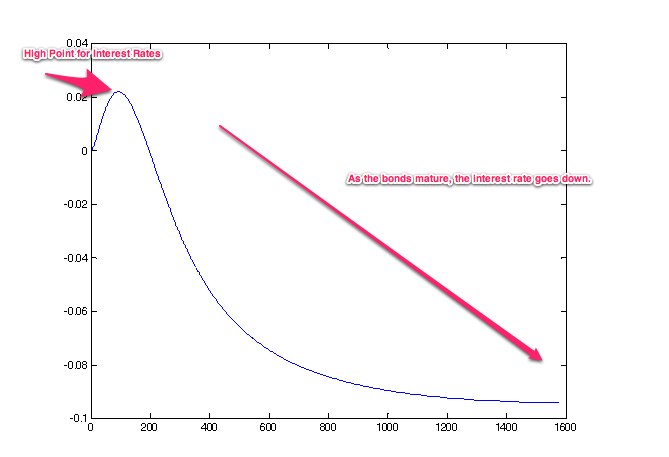

Econbrowser, a website that analyzes current economic trends, tried to predict the effect the maturing bonds would have before the operation went into affect September 21st.

The horizontal axis is weeks of maturity, and the vertical is the yield, or comparative worth, of the bond. Econbrowser determined that after an initial peak, the interest rates would drop dramatically.

The horizontal axis is weeks of maturity, and the vertical is the yield, or comparative worth, of the bond. Econbrowser determined that after an initial peak, the interest rates would drop dramatically.

So September 21st came and went, and the Federal Reserve implemented Operation Twist. Did it stimulate the economy? Did investors run to the market, capitalizing on long-term investing? In other words, was it a failure or a success?

Both, actually.

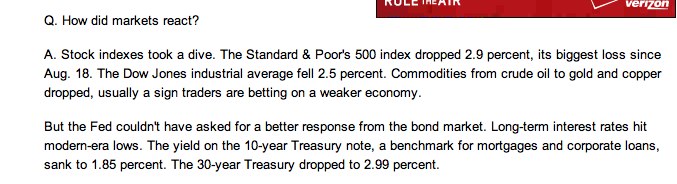

The stock market index took the worst dive it had in over a month. The bond market, however, saw long term investment rates drop immediately. A question and answer from the Seattle Times elaborates:

ReutersVideo expanded on the boon the bond market experienced:

ReutersVideo expanded on the boon the bond market experienced:

Though long term investment rates hit a record low, as mentioned in the video above, no one is quite sure who is benefitting yet. The overwhelming response from investors seem to be luke-warm at best.

As Matt Busigin, an ametuer economist and author of Macro Fugue analytics, tweeted:

Colin Cunningham than tweeted:

In the aftermath, Twitter was full of bad puns and indifference. Still, it is too early to tell the true effect Operation Twist will have on the U.S. economy. Though it achieved what it set out to do – lower long-term interest rates – it is still unclear whether the proposed boost of borrowing and investing will pan out.

Like the twist itself, we can only move back and forth on that question for now.

While Ernest Hemingway tossed and turned in his Idaho grave, Spanish animal rights activists and nationalists the world over celebrated Catalonia’s final bullfight.

While Ernest Hemingway tossed and turned in his Idaho grave, Spanish animal rights activists and nationalists the world over celebrated Catalonia’s final bullfight.